Key findings

A global movement to make government “open by default” picked up steam in 2013 when the G8 leaders signed an Open Data Charter - promising to make public sector data openly available, without charge and in re-useable formats. In 2014 the G20 largest industrial economies followed up by pledging to advance open data as a tool against corruption, and the UN recognized the need for a “Data Revolution” to achieve global development goals.

However, this second edition of the Open Data Barometer shows that there is still a long way to go to put the power of data in the hands of citizens. Core data on how governments are spending our money and how public services are performing remains inaccessible or paywalled in most countries. Information critical to fight corruption and promote fair competition, such as company registers, public sector contracts, and land titles, is even harder to get. In most countries, proactive disclosure of government data is not mandated in law or policy as part of a wider right to information, and privacy protections are weak or uncertain.

Our research suggests some of the key steps needed to ensure the “Data Revolution” will lead to a genuine revolution in the transparency and performance of governments:

-

High-level political commitment to proactive disclosure of public sector data, particularly the data most critical to accountability

-

Sustained investment in supporting and training a broad cross-section of civil society and entrepreneurs to understand and use data effectively

-

Contextualizing open data tools and approaches to local needs, for example by making data visually accessible in countries with lower literacy levels.

-

Support for city-level open data initiatives as a complement to national-level programmes

-

Legal reform to ensure that guarantees of the right to information and the right to privacy underpin open data initiatives

Over the next six months, world leaders have several opportunities to agree these steps, starting with the United Nation’s high-level data revolution in Africa conference in March, Canada’s global International Open Data Conference in May and the G7 summit in Germany this June. It is crucial that these gatherings result in concrete actions to address the political and resource barriers that threaten to stall open data efforts.

In detail

From our sample of 86 countries, representing a wide range of political, social and economic circumstances we find that:

-

Open data initiatives that receive both senior-level government backing and sustained resources are much more likely to achieve impact. This demonstrates that Open Government Data (OGD) initiatives, as they become established, can provide a clear return on effort and investment.

-

Much more needs to be done to support data-enabled democracy around the world. There has been very limited expansion of transparency and accountability impacts from OGD over the last year. Of the countries included in the Barometer, just 8% publish open data on government spending, 6% publish open data on government contracts, and a mere 3% publish open data on the ownership of companies. Citizens have a similarly difficult time accessing data on the performance of key public services — just 7% of countries release open data on the performance of health services, and 12% provide corresponding figures on education.

-

To maximise impact, open data needs go local. Political impacts from open data are greater in countries that have city-level open data activities. Widespread availability of data skills training is also correlated with higher political impact.

-

Global progress towards embedding open data policies stalled in 2014. While many countries with moderate or strong OGD initiatives in 2013 have seen steady growth in the availability and impacts of OGD, a number of countries have slipped backwards over the last 12 months. Many of the countries that made initial steps with OGD in 2012/13 have not sustained their OGD commitments and activities. Government that is “open by default” is a long way off for most of the world’s citizens.

-

A small number of countries are moving towards requiring proactive disclosure of government data as part of their Right to Information (RTI) laws — effectively establishing a Right to Data. This should be welcomed. However, the open data policies of most countries continue to lack legislative backing. The continued weakness of data protection laws — particularly in light of continued revelations and concerns about data mining by corporations and states — is a cause for concern.

-

For data to be considered truly open, it must be published in bulk, machine-readable formats, and under an open license. This year, just over 10% of the 1,290 different datasets surveyed for the Barometer met these criteria — a small but significant increase from 2013, when 7% of datasets were published in full open data format. Thirty-one countries have at least one open dataset, and just over 50% of the datasets surveyed among the 11 top-ranked countries qualified as fully open.

Country by country analysis

Based on a cluster analysis of our OGD readiness and impact variables we divide countries studied into four groups:

-

High capacity - These countries all have established open data policies, generally with strong political backing. They have extended a culture of open data out beyond a single government department with open data practices adopted in different government agencies, and increasingly at a local government level. These countries tend to adopt similar approaches to open data, incorporating key principles of the open definition, and emphasising issues of open data licensing. They have government, civil society and private sector capacity to benefit from open data.

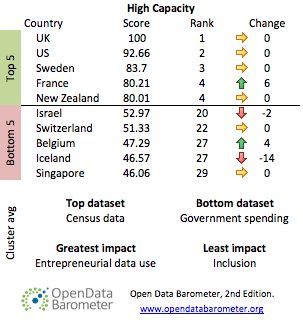

Countries included in this cluster in ODB rank order are: UK, US, Sweden, France, New Zealand, Netherlands, Canada, Norway, Denmark, Australia, Germany, Finland, Estonia, Korea, Austria, Japan, Israel, Switzerland, Belgium, Iceland and Singapore. While this year’s top five includes three of the signatories of the 2013 G8 Open Data Charter (UK, US and France), the rest of the G8 languish much lower in the rankings, with Japan, Italy and Russia not even making the top ten.

-

Emerging & advancing - These countries have emerging or established open data programmes — often as dedicated initiatives, and sometimes built into existing policy agendas. Many of these countries are innovating in the delivery of open data policy, contextualising open data for their populations by, for example, focussing on the need for governments to make data visually accessible in contexts of limited literacy and data literacy, such as India, or by exploring the linkages between RTI laws and open data, as in the Philippines. The countries in this cluster have a variety of different strengths and have great potential to develop innovative approaches to open data. However, many still face challenges to mainstreaming open data across government and institutionalising it as a sustainable practice.

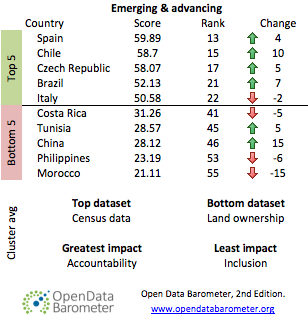

Countries included in this cluster, in ODB rank order, are: Spain, Chile, Czech Republic, Brazil, Italy, Mexico, Uruguay, Russia, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Hungary, Peru, Poland, Argentina, Ecuador, India, Colombia, Costa Rica, South Africa, Tunisia, China, the Philippines and Morocco.

-

Capacity constrained - The countries in this cluster all face challenges in establishing sustainable open data initiatives as a result of: limited government; civil society or private sector capacity; limits on affordable widespread Internet access; and weaknesses in digital data collection and management. A small number of the countries in this cluster, such as Kenya, Ghana and Indonesia, have established open data initiatives, but these remain highly dependent upon a small network of leaders and technical experts. Without sustained leadership and investment, moves towards open data are difficult to make sustainable, as Kenya’s dramatic fall in the Barometer rankings demonstrates. Limited availability of relevant training and technical capacity for working with open data presents an extra challenge for these countries. There is an urgent need for more appropriate models of education and capacity building that can support nascent community and government-led open data initiatives. These countries are most in need of a comprehensive data revolution, including, in many countries, attention to basics of Internet connectivity and data literacy.

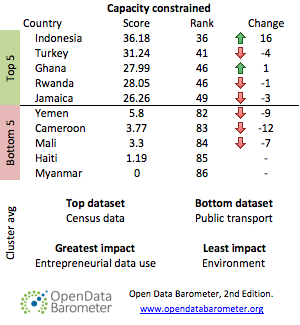

Countries included this cluster, in ODB rank order, are: Indonesia, Turkey, Ghana, Rwanda, Jamaica, Kenya, Mauritius, Ukraine, Thailand, Vietnam, Mozambique, Jordan, Nepal, Egypt, Uganda, Pakistan, Benin, Bangladesh, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania, Venezuela, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Zambia, Yemen, Cameroon, Mali, Haiti and Myanmar.

-

One-sided initiatives - These countries each have some form of open data initiative, ranging from departmental web pages that display open data, to full open data portals. However, government action to publish selected datasets is not matched by civil society capacity and freedom to engage with the data, nor by private sector involvement in the open data process. As a result, these initiatives appear to be very supply-side driven, without engagement with a broad community of users. Without wider political freedoms, the potential of open data to bring about political and social change in these contexts will be limited.

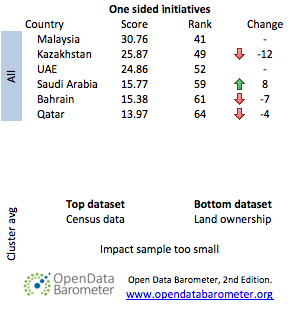

The countries in this cluster, in ODB rank order, are: Malaysia, Kazakhstan, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Qatar.

Moving forward

Different strategies will be needed in each cluster in order to develop and deepen effective open data practice. While the “big tent” of open data, the well networked open data community, and the availability of shared guides, tools, and technologies, have all helped the open data concept to spread rapidly, there is no single “best practice” for delivering an open data initiative. Continued innovation and evaluation is needed to find best-fit approaches to apply in relation to different countries, communities, datasets and goals for open data policy.

The rest of this report looks in depth at different aspects of the open data landscape, before providing an aggregated ranking of country performance on readiness, implementation and impact.

Get the Data

The Open Data Barometer is part of ongoing, open research. All the data underlying this report is available for further analysis and re-use.

Visit the download the data pages for more information.