Global rankings

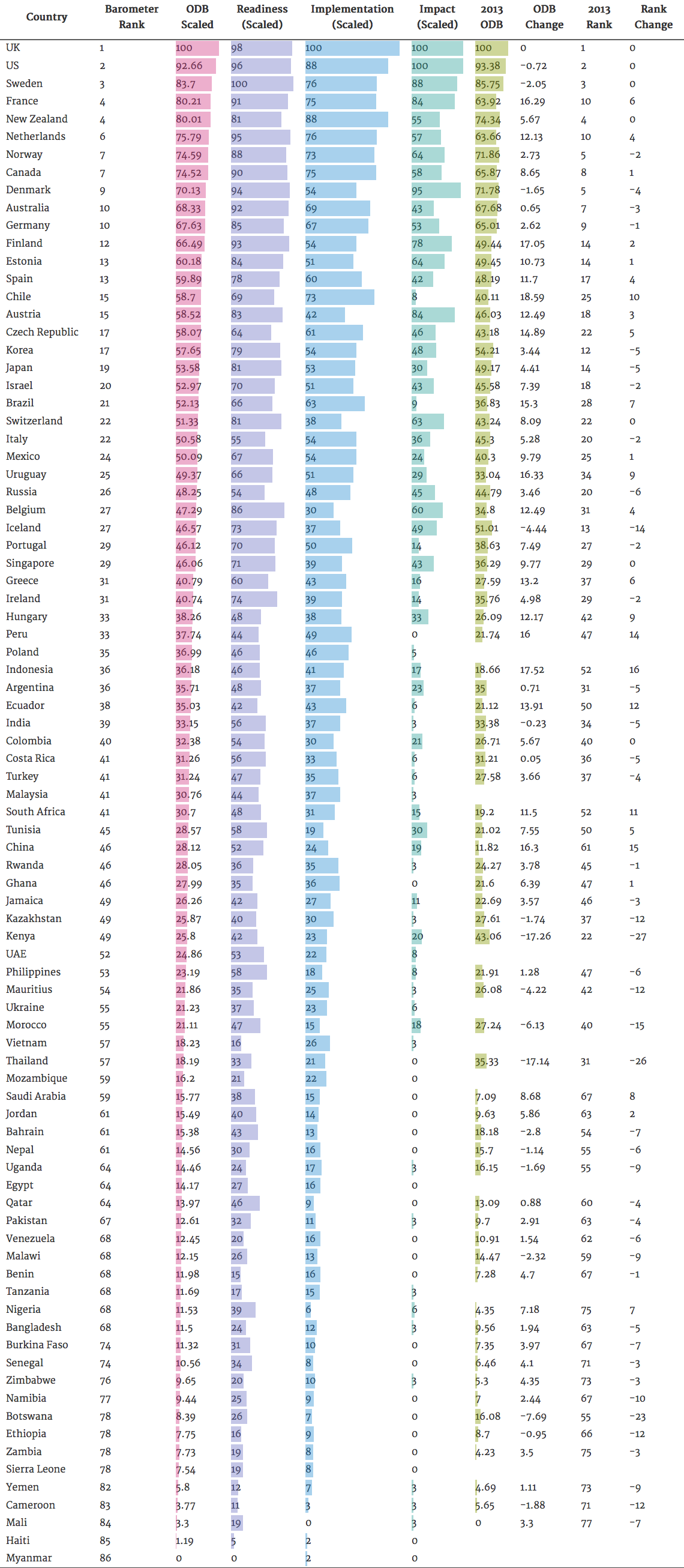

To create a global ranking, we aggregated the sub-indexes of the Open Data Barometer. Comparing scores and ranks in the second edition with those in the first can help to identify countries making progress, and those where progress has stalled.

As this year’s Barometer covers 86 countries (compared with the 77 countries covered in 2013), a change in rank position may result both from new countries entering the assessment above or below the score of a previously included country, as well as from substantial changes to that country’s score.

The table below presents the global rankings of the Open Data Barometer, including the overall Barometer score, as well as comparisons between the first and second editions of the Barometer. You can sort and filter this table, and group by various facets, including country clusters, region and income level.

Scaled country scores are rounded to the nearest whole number before ranks are assigned, meaning a number of countries receive tied rankings.

Analysis

In this section, we analyse the rankings and the changes between the first and second editions of the Open Data Barometer. The purpose here is not to provide an exhaustive account of all changes, but to identify notable trends, and to explore the extent to which the Barometer can act as a useful heuristic for understanding the changing landscape of open data around the world.

Just 16 of the 77 countries (20%) included in the 2013 Open Data Barometer saw a reduction in their scaled ODB score in this 2014 edition. In general, the trend is towards steady, but not outstanding, growth in open data readiness and implementation. However, the picture varies substantially across the different country clusters.

Capacity constrained

In the capacity constrained cluster, Indonesia and Nigeria saw the strongest growth in ODB score and rank; Kenya experienced the largest fall in rank. In countries with civil society-led activities, such as Nepal and Uganda, the continued limits on government engagement with their open data initiatives caused minor score reductions.

Indonesia’s role as lead chair of the Open Government Partnership in 2013/14 focussed both domestic and international attention on the development of open data policy and practice in the country. There has been growing civil society engagement around open data, particularly in urban centres like Jakarta, and some increase in the availability of capacity building training and support for innovation.

In Nigeria, the Minister of Communication Technology launched an OGD initiative in January 2014, with a series of engagement activities designed to involve stakeholders in shaping the country’s policies, and to provide training and capacity building for potential data users1. This federal-level initiative, supported by the World Bank and the UK Department for International Development (DFID), followed on from the first state-level initiative in Africa launched in the state of Edo in September 20132. A number of civil society organisations in Nigeria have sought to develop information and advocacy based work with open data, including BudgIT who work to simplify and communicate the Nigerian budget, and Follow The Money who have developed a series of campaigns tracking aid and government finance, including a successful and ongoing campaign to secure the distribution of funds pledged to clean up lead-poisoned land in Zamfara state3. The University of Ilorin in Nigeria has also been exploring ways to build student capacity to engage with open data — the Computer Science Department has hosted hackathons and, following participation in the Web Foundation’s Open Data in Developing Countries project, established an Open Data Research Group.

At the other end of the table, Kenya has fallen 27 places in the overall rankings, and has seen a reduction in scaled ODB score from 43 to 26. While many hoped that the high-profile launch of an open data portal in 2011 would be followed by ongoing commitment and a policy framework for open data, no such framework has come into force, and few updates have been made to the data on the portal over recent years. The stagnation of Kenya’s open data activities has been the topic of much discussion, including by some of the lead architects of its open data movement, who argue for a renewed commitment to open data that builds on legislative foundations in the country’s Right to Information and Data Protection Laws4. Kenya has also gone through a process of constitutional reform, devolving power to local governments. While this presents an important opportunity to design new infrastructures of administrative data management which apply “open by default” principles, there is little evidence that this is happening. The failure of Kenya to sustain the supply of timely and relevant open data, and the limited sustainability and scalability of applications built by local developer communities using government data5 should raise significant questions about the appropriate design of open data initiatives in capacity constrained countries.

There are considerable similarities in the readiness levels of Nigeria, Indonesia and Kenya. Whether the open data initiatives adopted in Nigeria and Indonesia can be sustained beyond initial donor investments and interest may depend on whether the models used can shift from simply transplanting practice from higher capacity countries, to developing open data practices that respond to the local availability of technical intermediaries, the capacities of different parts of government, and the local social dynamics of information access and trust6. Ghana also provides a useful point of comparison — open data supply has increased, but the impacts of this data availability are yet to be seen. Ghana experienced a minor drop in readiness in this year’s Barometer, primarily as a result of limited attention to open data following the country’s 2012 launch of an open data initiative. While the last year has seen steady growth in open data availability from data.gov.gh, there is little evidence of community engagement at present, and the Barometer records no evidence of impacts from open data use in Ghana.

Two countries that have been exploring alternative models for open data are Nepal and Uganda. Both countries have created civil society networks — Open Nepal and Open Development Uganda — and have created their own data portals independent of government7. The Open Data Barometer’s current focus on government data activities does not fully capture these efforts in the quantitative scoring, though there have been efforts to engage with government in each country, including through technical agencies and specific ministries. These initiatives points towards one possible future for an inclusive data revolution — one in which open data initiatives are developed as equal multi-stakeholder partnerships between civil society, government, donors, and social entrepreneurs, cooperatively working to increase the quantity and quality of data available to improve decision making by all parties. However, the extent to which current models of support and financing for open data activities are set up to enable growth of such models is unclear.

Countries to watch in the coming year in this cluster include Botswana, where an open data readiness assessment was recently undertaken8, although it currently lacks a Right to Information law; and Sierra Leone, who also has the potential to develop open data activities over the coming year — the country recently passed a Right to Information law and is exploring ways to integrate open data into the roll out of the new RTI processes, and to make data accessible in both digital and non-digital formats9.

Emerging and advancing

The last year has seen considerable growth in the availability of data, as well as minor growth in impacts and gains in readiness, among emerging and advancing economies. All the countries in this cluster should have the domestic resources to institutionalise OGD practices, but need to continue to build broad-based political and civil society support in order to effectively embed open data.

In this cluster, Chile, Uruguay, China, Peru, Brazil, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Greece, Hungary, Spain, South Africa, and Mexico all saw growth in terms of readiness and implementation. Progress was more moderate in Colombia, Ireland, Italy, the Philippines, Portugal, Russia and Tunisia, and changes in Argentina, Costa Rica and India are within the margin of error of the study. Poland, which is included in the ODB for the first time in this edition, ranks roughly at the centre of this group — in 35th overall position — with reasonable levels of readiness and impact, but low perceived impact from open data.

China experiences one of the highest ODB score changes in this cluster, compared to 2013. The survey records an increase in the readiness of entrepreneurs in China to engage with open data, as well as continued growth of city-level initiatives, such as in Beijing, Shanghai, Qingdao City, Wuhan City and Guangzhou Municipality. These initiatives often link the concepts of open data and big data, looking to draw on the technical capacity of the state, and entrepreneurs outside the state, to drive greater efficiency of governing through data. This is reflected in China’s strongest open data impact score relating to increasing government effectiveness and efficiency. The survey also identifies cases of companies who previously had to buy government data but are now able to access it for free as a result of new practices, thereby contributing to greater economic surplus. China has also seen growth in the availability of environmental information over the last year, at least in part due to citizen action, with infzm.com reporting that citizen-led science projects to measure water quality successfully pressured officials to disclose water quality data10. However, although the increase in social policy dataset availability is notable, accountability datasets remain almost completely absent, highlighting the extent to which countries may seek to selectively pursue open data policy, without releasing a full spectrum of data.

The strong growth in ODB position among Latin American countries within this cluster reflects growing momentum around open data on the continent, where substantial developments are also being seen at the city level11. In Uruguay, for example, researchers cite the strong push for open data from the government of the city of Montevideo, which serves almost half the population of the country,12 as an influence on national level progress. The region also has relatively strong engagement between government and civic technology communities — regional events like Condatos attract participants from all sectors, and a number of countries regularly run hackathons, ideation events, and other technically oriented engagement activities. The strength of open source communities and cultures plays a role in supporting engagement with the concept of open data. A focus on data journalism is also a notable feature of the landscape in a number of Latin American countries, with traditional and emerging media exploring how data can be used to uncover stories on government activities. In a break from the common pattern of just new technology-centric civil society networks and organisations focussing on open data, mainstream civil society organisations in Argentina, such as the Centro de Implementación de Políticas Públicas para la Equidad y el Crecimiento (CIPPEC), have developed open data activities and focussed attention on new areas — in particular looking to extend the application of open data from the executive to the judicial branch of government13.

Brazil is one of a number of governments thinking in terms of the creation of a ‘National Infrastructure for Open Data’, setting out clear processes for the institutionalisation of open data policy. Much like the open approach of Project Open Data in the USA, the Brazilian INDA project has established an open collaboration space, oriented towards the involvement of technical communities in setting meta-data standards, building out open data technologies, and modelling data.

In reviewing Open Data Barometer scores across Latin America, it is notable that limited use of open licenses acts as a downward pressure on the implementation scores achieved for countries in the region. Qualitative research into the supply and use of budget data in Brazil has noted the low levels of awareness of licensing issues amongst data publishers and users, raising questions as to how important license issues are to open data within the Brazilian, and wider regional, context 14.

Tunisia, Morocco and South Africa are the only African countries to feature in this cluster. In spite of the potential resources to support an OGD initiative in South Africa — both in terms of government capacity and civil society and private sector capacity — the country has not yet established a national project, nor does it include commitments to open data in its Open Government Partnership National Action Plan 15. However, the Western Cape provincial government is working on a provincial open data policy — potentially providing foundations for future national efforts — and the City of Cape Town adopted an open data policy in September 201416. These developments were cautiously welcomed by civil society, although some expressed concerns around licensing and review mechanisms17.

Tunisia established an open data portal in 2012, and has continued to maintain the site. However, research suggests there is limited engagement with civil society users, and that the open data user community has not expanded substantially over the last year, leading to only moderate growth in Tunisia’s overall score. Perceived political impacts of the Tunisian OGD initiative have also fallen in this year’s Barometer, suggesting a widening gap between the hope for the portal as part of building a transparent democratic state, and the current reality.

Morocco’s ODB score has also fallen in this edition. Though Morocco was the first country in Africa to establish a data portal, the quality, timeliness, and relevance of the datasets currently being made available is limited. There is some evidence of community engagement between government and groups, such as the local Open Knowledge Foundation, but an evaluation of the initiative noted that “despite its innovative nature, the Moroccan open data initiative did not enjoy the interest it deserved; the released datasets are/have remained very limited. This situation is certainly related to the fact that the initiative has been led by a governmental entity … in a very isolated fashion, without being inscribed in any true governmental strategy and [promoted] through a very insufficient communication”18

The European countries included in this cluster include, in rank order, are Spain, Czech Republic, Italy, Russia, Portugal, Greece, Ireland, Hungary and Poland. Common across all these countries, with the exception of Russia, is a greater level of civil society readiness vis-a-vis the readiness of government or entrepreneurs, and a lower level of perceived social impact from open data. This low level of government readiness may reflect the absence of a substantive OGD initiative, as in Poland, or may identify contexts where initiatives are established, but are progressing relatively slowly when compared to the rest of Europe, such as in Spain. In this group, the Czech Republic has seen the strongest growth in its overall ODB score, with efforts underway to embed open data in government, including a proposed draft amendment to embed open data concerns and develop a cross-governmental policy on open data in the country’s Freedom of Information Bill.

The picture in Russia is shaped by the increased availability of a number of datasets, boosting its implementation scores, while government and civil society readiness to benefit from open data has seen a marginal decrease, matched by decreases in social and political impact.

Among Asian countries in this cluster, both India and the Philippines have seen only small changes in their ODB scores. This result is somewhat surprising given the launch of an OGD initiative in the Philippines in January 2014, and India’s ongoing OGD initiative. However, the ODB survey suggests the increase in readiness in the Philippines has been offset by slow progress translating readiness into core dataset availability and impacts over the last year. This highlights the potential lag time between initiatives and their effects. In India, the 2012 National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy19 and early engagement efforts around the data portal do not appear to have been extended, and open data remains a niche subject that has not yet reached the awareness of most of the potential users.

High capacity

Each of the countries in the high-capacity cluster has observed some impacts from open data over the last year, and the general trend is towards increased readiness and implementation of open data. However, examining the rankings, a number of countries stand out from the general trend, with either substantial ranking gains or falls.

France enters the top five, rising six places from their tenth place ranking in 2013 to a fourth place ranking this year. In May 2014, France announced it would be the first European country to appoint a Chief Data Officer20, responsible for:

- Better organising the flow of data within the economy and within the administration - while also respecting privacy and legal restrictions on data sharing;

- Ensuring the production or acquisition of key data;

- Launching experiments to inform public decision making; and

- Disseminating the tools, methods and culture of data within government departments and in support of their respective goals.

In the same year that the UK Government sold off the vitally important Postal Address File as part of the privatisation of the national mail service21, and Canada continues to resist requests to make post code data available, La Poste in France made post codes available as open data22, suggesting a willingness to focus on the availability of high value datasets. Considerable outreach activities and a growth of well-resourced municipal open data initiatives have also contributed to France’s rise in the Barometer tables. The challenge ahead for France — which received relatively low impact scores on the social and environmental benefits of open data, and is preparing to deliver its first Open Government Partnership National Action Plan in early 2015 — will be to further broaden open data out beyond administrative and technical communities, and to translate open data availability into diverse uses and impacts.

Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands have each moved three or more places up the Barometer rankings. After the federal election in late 2013, Austria’s new government included open data in its coalition agreement23, but researchers reported that, as of August 2014, no member of the cabinet could be identified as in charge of the subject. In general, the Austrian open data agenda appears to be driven by several major cities and regions; in centres such as Vienna, start-up activity around open data is generating social, economic and environmental returns. The application Solarize, for example, available for Upper Austria and based on open datasets, is designed to help people understand the benefits of having their own solar or photovoltaic generation24.

In both Belgium and the Netherlands, open data policy is supported by a strong push from organised civil society groups, as well as support from those groups to stimulate the use of open data through hackathons and other activities. Researchers identified a much greater rate of open data publication in the Netherlands, where almost 50% of datasets surveyed qualified as open under the open definition. However, there was greater optimism about the potential impacts of open data in Belgium, albeit a decrease in perceived impacts of open data on accountability.

Finland has also experienced substantial growth in its overall Barometer score. As the host of the 2012 Open Knowledge Festival, strong links appear to have been built in Finland between civil society, government, and businesses, establishing broad awareness of open data in the media, among civil society actors, and among certain sections of the business community. This second edition of the Barometer also indicates increased impact of open data in Finland, although as yet there has not been an in-depth evaluation of the open data policy’s impacts to verify anecdotal evidence.

Israel, Japan, Korea, Norway, Germany and Australia all have seen more modest changes in their overall scores, although in a number of cases, as other countries move ahead faster, this has led to drops in their overall ranking. Denmark and Iceland both experienced modest reductions in their scores and rankings — mostly as a result of weaker implementation — which appear to be in part correcting for some over-scoring of dataset openness in these countries in 2013. As the rankings table above shows, countries towards the top of the Open Data Barometer have very similar readiness, implementation, and impact scores, making the highest rankings open to just about any country in the high-capacity cluster. In future editions of the Barometer, new variables may be required to better discriminate between high-capacity countries, and to identify the key areas for further attention and progress.

The UK, USA and Sweden remain at the top of this cluster, and at the top of the Barometer overall. Each country has placed an emphasis on the economic growth potential of open data and, over the last year, each has continued to develop mechanisms for engaging with private sector data users — from the Open Data User Group in the UK, to the Open Data Forum convened by the Ministry and Enterprise in Sweden, and the Open Data Roundtables series convened by the GovLab at NYU in partnership with the US Federal Government. They have also focussed on gathering stories of business re-use of open data, contributing to strong economic impact scores. Some fears have been raised that this emphasis comes at the cost of a focus on the social and environmental impacts of data. While an analysis across our data suggests support for innovation in general is correlated with social and political impacts, these can also be more explicitly designed for, with specific attention paid to including diverse actors in shaping data supply, and benefiting from capacity building.

There remain many issues for Barometer leaders to work on. For example, open data licensing in Sweden is still applied inconsistently, and in the UK, flagship datasets, such as transactional level spending for government departments, is often — according to the government’s own dashboard — out of date, limiting the utility of this for scrutiny of government25. Over the last year, the US website data.gov has been re-launched with a stronger slant towards developer communities, suggesting that early efforts at broad community engagement have not taken root, and highlighting a need for sustained activity to take open data beyond the technical and developer communities to reach out to the full community of potential users.

One-sided initiatives

The small number of countries clustered under ‘one-sided initiatives’ all have high levels of Internet penetration, high or upper-middle income status, and strong government capacity. All lack Right to Information laws. In most cases there is also a reasonable level of government capacity. However, civil society freedoms and capacity are very limited in this cluster, as is the breadth of data published by governments. The outlier in this group may be Malaysia, which is the highest ranked country in this cluster (and perhaps the weakest fit in the cluster, as the Freedom House measure of civil society freedoms used in the readiness component scores of the Barometer scores Malaysia almost 100% higher than others in the cluster). The Malaysian open data initiative currently provides over 100 datasets from 11 different ministries. However, researchers note that there has been very little outreach to engage users with the data, or to prioritise the publication of those datasets most in demand. The lack of a Right to Information law further undermines space for the initiative to be demand-driven, rather than implemented top-down by government.

The UAE scores highest on readiness in this cluster, in part because of policy commitments that have been made to open data within the framework of well-funded e-government reforms. This equation of open data with an e-government, rather than an open government paradigm, is characteristic of engagement with open data within the Gulf States, and is reflected in the fact that even though the countries in this cluster have reasonable levels of readiness among entrepreneurs to engage with data, few economic impacts have yet been identified, and social impact is very weak. A broader framing of open data as associated with “[supporting] the … National Development Strategy 2011-2016’s call for Transparency, Efficiency and Participation of its people” was present in a March 2014 consultation on open data policy in Qatarr26, though the translation of this into the availability of key transparency, accountability and social policy datasets remains to be seen.

Conclusions

In this report we have only been able to explore a small fraction of the data captured by our surveys. While high-income, high-capacity countries are continuing to embed open data policies, albeit with increasing focus on economic rather than civic aspects, across the rest of the world, the picture that emerges is one of a widening gap between those able to establish and sustain open data programmes, and those countries where open data activities have stalled, moved backwards, or not yet begun. As data becomes ever more important in shaping policy debates, the importance of citizens having effective access to data grows; yet without dedicated efforts, the unfolding “data revolution” risks leaving many behind.

Our findings also suggest that the answers do not lie in taking models and “best practices” from high-capacity countries alone — there are many lessons to be learned from countries with emerging and advancing open data initiatives, and critical lessons to learn from successes and failures in capacity constrained countries. If we trust that the idea of “open by default” is becoming widely established, then the challenge we face now is to innovate, building towards a second wave of focussed and intentional open data initiatives, and to invest time and energy in putting the idea of “open by default” on firm foundations. This requires not only developments in open data practice, but also developments in how it is measured and monitored.

Effectively capturing the potential of open data initiatives to reduce corruption, improve public services and governance, and empower citizens will require world leaders to take a series of concrete actions to address the political and resource barriers that threaten to stall open data efforts. High-level political commitment is essential to guaranteeing the proactive and disclosure of fully open government data — that is, data that can be freely used, modified and shared by anyone, and that is available free of charge. The requirement to disclose and regularly update this data should be mandated in law or policy as part of a wider right to information, and governments at the same time should guarantee that strong privacy protections are in place and respected. Governments will further need to ensure that investment in and support of both city- and national-level programmes is consistent and sustained beyond initial open data efforts. In addition to mandating the supply of OGD, governments must work to enhance the ability of civil society and entrepreneurs to understand and use the data effectively; this can be accomplished through trainings, as well as the contextualisation of open data tools approaches to local needs.

Through this two-year pilot of the Open Data Barometer we have established a corpus of data that can support further in-depth research to understand the dynamics of open data. By going beyond counting datasets and recognising that openness has many dimensions, our hope is that this work contributes to dialogue about the kinds of openness citizens want, and to critical activity that helps build better and more inclusive open data initiatives.

Footnotes and references

-

Punch NG, (Jan 31st 2014), Govt commences open data initiative http://www.punchng.com/business/business-economy/govt-commences-open-data-initiative/ ; Government of Nigeria, (Jan 29th 2014), FG Kicks Off Open Data Initiative http://commtech.gov.ng/index.php/videos/news-and-event/128-fg-kicksoff-opendata-initiative ↩

-

Channels Television (Sept 13th 2013), Edo Launches First Open Data Portal In Nigeria, http://www.channelstv.com/2013/09/13/edo-launches-first-open-data-portal-in-nigeria/ ↩

-

The #SaveBagega campaign addressed delays in allocating pledged funds to the clean-up of lead poisoning in Northern Nigeria. Through budget data visualisation and mobilising popular attention, the campaign sought to pressure the government to disburse pledged funds, and has maintained ongoing tracking of spending on the clean-up operation. http://followthemoneyng.org/savebagega.html ↩

-

NDemo, Bitange (Nov 24th 2014), Open contracting format can clean up government procurement http://www.nation.co.ke/oped/blogs/dot9/ndemo/-/2274486/2532264/-/1wpu9kz/-/ ↩

-

Mutuku, Leonida, and Christine Mahihu. (2014) Understanding the Impacts of Kenya Open Data Applications and Services. http://opendataresearch.org/sites/default/files/publications/ODDC%20Report%20iHub.pdf. ↩

-

See for example Chiliswa, Zacharia. (2014) Open Government Data for Effective Public Participation: Findings of a Case Study Research Investigating The Kenya’s Open Data Initiative in Urban Slums and Rural Settlements, http://opendataresearch.org/sites/default/files/publications/JHC%20Publication%20April%202014%20-%20ODDC%20research.pdf. which explores patterns of information access and use in rural and urban slums in Kenya, and which raises important considerations for ↩

-

E.g. http://data.opennepal.net/datasets and http://catalog.data.ug/dataset ↩

-

Botswana Innovation Hub (June 10th 2014) The Open Data Readiness Assessment - http://www.bih.co.bw/detail.php?id=220 ↩

-

Abdulai, E (May 26th 2014) Connecting Open Data and the Right to Information in Sierra Leone http://www.opendataresearch.org/content/2014/642/connecting-open-data-and-right-information-sierra-leone ↩

-

汪韬,家乡水,清几许?,南方周末,(Feb 13th 2014) http://www.infzm.com/content/98057 Accessed June 18 2014. ↩

-

For an account of open data in four Latin American cities, and the different top-down and bottom-up models being adopted, see the collection of ‘Opening the Cities’ case studies from the Open Data in Developing Countries project: http://www.opendataresearch.org/project/2013/cities ↩

-

Based on http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=population+of+uruguay%2C+population+of+montevideo ↩

-

Elena, Sandra, Natalia Aquilino and Ana Riviére (2014) Emerging Impacts in Open Data in the Judiciary Branches in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay, http://www.opendataresearch.org/sites/default/files/publications/Case%20study%20-%20CIPPEC.pdf. ↩

-

Beghin, Nathalie, and Carmela Zigoni (2014). Measuring Open Data’s Impact of Brazilian National and Sub-National Budget Transparency Websites and Its Impacts on People’s Rights, http://opendataresearch.org/sites/default/files/publications/Inesc_ODDC_English.pdf. ↩

-

South Africa OGP National Action Plan (2013) http://www.opengovpartnership.org/sites/default/files/OPG%20booklet%20final%20single%20pages.pdf ↩

-

City of Cape Town Open Data Policy (2014) http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/Policies/All%20Policies/Open%20Data%20Policy%20-%20%28Policy%20number%2027781%29%20approved%20on%2025%20September%202014.pdf ↩

-

Eyal, A. Cape Town’s Open Data Policy, Time to Celebrate? (2014) http://code4sa.org/2014/09/27/capetown-opendata-policy.html ↩

-

Maghreb Digital (2013) Rapport Open Data : a libération des données publiques au service de la croissance et de la connaissance http://www.maghreb-digital.com/projet/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Open-Data-Maroc.pdf ↩

-

Chattapadhyay, S. (2013). Towards an Expanded and Integrated Open Government Data Agenda for India. In ICEGOV2013. Seoul, Republic of Korea: ACM Press. doi:10.1145/2591888.2591923 http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2591888.2591923 ↩

-

EtaLab (May 21st 2014) Ouverture des données publiques : création de la fonction d’administrateur général des données (chief data officer) https://www.etalab.gouv.fr/ouverture_des_donnees_publiques_creation_de_la_fonction_dadministrateur_general_des_donnees_chief_data_officer ↩

-

Arther, Charles (March 17th 2014) MPs and open-data advocates slam postcode selloff http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/mar/17/mps-and-open-data-advocates-slam-postcode-selloff ↩

-

EtaLab (Nov 14th 2014) La base officielle des codes postaux est disponible sur data.gouv.fr https://www.etalab.gouv.fr/la-base-officielle-des-codes-postaux-est-disponible-sur-data-gouv-fr ↩

-

Austrian Federal Chancellery (Dec 2013) Work programme of the Austrian Federal Government 2013–2018 https://www.bka.gv.at/DocView.axd?CobId=53588 ↩

-

https://www.data.gv.at/anwendungen/solarize/ / http://solarize.at/en/ ↩

-

http://data.gov.uk/data/openspending-report/index ↩

-

ICT Qatar (2014) Public Consultation on draft Open Data Policy http://www.ictqatar.qa/en/documents/document/public-consultation-draft-open-data-policy ↩